Inside Jaeger-LeCoultre: A Day Among Masters

Exploring the Reverso workshop, the full in-house manufacture, and the soul of Swiss watchmaking

Welcome back to The Deadbeat Seconds. This week’s article is a little different. I’m writing about an incredible experience I recently had in Switzerland at the Jaeger-LeCoultre manufacture. I booked the Reverso Discovery Workshop, flew into Geneva, drove out to the Vallée de Joux, and had an unforgettable time. If you’re thinking about doing something like this, just go for it. It was even better than I had hoped.

And don’t worry, I still love Lange. July’s list of the top five Lange watches on the market will be out this weekend. In the meantime, sit back and enjoy the ride.

Before we get started, I should mention that this entire trip was self-funded. Flights, hotel, and the workshop at the manufacture were all paid for out of my own pocket. Nothing was sponsored by Jaeger-LeCoultre, so as always, you can expect a completely unbiased perspective.

If you love watches, sooner or later, all roads lead to Switzerland. But it’s not Geneva, Zurich or Basel that truly beats as the heart of haute horlogerie- it’s a secluded valley nestled deep in the Jura Mountains. The

Vallée de Joux. This is where time is made.

The Valley That Built the Industry

Nestled in the Jura Mountains of western Switzerland, near the French border, lies the Vallée de Joux- a remote alpine plateau that has shaped the trajectory of fine watchmaking for more than two centuries. It’s a place of quiet winters, mirror-like lakes, and meticulous hands. But beyond its serene landscape lies a beating heart of horological innovation, craftsmanship, and legacy.

A Harsh Land, A Precise Craft

The Vallée de Joux was never supposed to be a cradle of luxury. Life here was hard. With an elevation of around 1,000 meters, winters were long, dark, and brutally cold. Farming was nearly impossible for much of the year. But hardship breeds ingenuity. And in the 18th century, the region’s inhabitants began turning to watchmaking not as art, but as economic necessity.

Families would spend the winter months crafting components in their homes: wheels, pinions, and springs, often sold to larger workshops or établisseurs in Geneva. Precision mechanics became the regional language, passed down from father to son, neighbor to neighbor.

By the early 19th century, the Vallée was no longer just a cottage industry supplier it was becoming a force of its own.

Antoine LeCoultre and the Birth of the Manufacture

No single figure represents the ascent of the Vallée de Joux quite like Antoine LeCoultre. Born in 1803 in Le Sentier, he embodied the region’s spirit of innovation and rigor. In 1833, LeCoultre founded a small workshop focused on precision tools and horological components. His breakthroughs would shape the entire industry.

In 1844, he invented the Millionomètre, the first instrument capable of measuring to the micron. This allowed for a new level of accuracy in part-making and set the standard for mechanical tolerances in watchmaking. Then, in 1847, he developed a keyless winding and setting mechanism—a foundational step toward modern wristwatches.

But perhaps his greatest contribution was structural: in 1866, together with his son Elie, he founded the first true manufacture in the region, unifying all watchmaking disciplines under one roof. From ébauches and escapements to finishing and casing, everything was done in-house. It was revolutionary.

This was the origin of Jaeger-LeCoultre, though the “Jaeger” name would only be added later in the 20th century after a fruitful collaboration with Parisian watchmaker Edmond Jaeger.

Today, Jaeger-LeCoultre remains the Vallée’s flagship institution- its “Grande Maison”- producing everything from three-hand dress watches to minute repeaters, tourbillons, and their signature innovation: the Reverso.

The Rise of the Complication Kings

As the Vallée de Joux matured, other powerhouses emerged, drawn by the pool of talent, tradition, and innovation.

Audemars Piguet, founded in 1875 in the village of Le Brassus, just down the road from Le Sentier, quickly gained a reputation for its complicated pocket watches. Jules Louis Audemars and Edward Auguste Piguet both hailed from long lines of local watchmakers and built their brand on the premise that no complication was too complex. Even today, AP remains one of the few brands that still produces grande complications entirely in-house, including perpetual calendars, split-seconds chronographs, and minute repeaters.

While Audemars Piguet would become globally synonymous with the Royal Oak in the 1970s, it has never abandoned its roots in traditional watchmaking, with its Atelier des Grandes Complications still based in the valley.

Blancpain, while historically based in Villeret, also has a crucial foothold in the Vallée de Joux. In recent decades, it has concentrated much of its complication work- including perpetual calendars and carrousels- at its Le Brassus facility. Blancpain’s integration into the Swatch Group has only increased the region’s profile, as high-end production was centralized there.

Breguet, under the Swatch Group as well, assembles many of its tourbillons and high-complication movements in the valley, leveraging the unique ecosystem of watchmakers that only the Vallée can offer.

The Vallée’s significance isn’t merely its roster of brands- it’s the density of talent. Nowhere else in the world do so many métiers converge: guilloché, engraving, enamelling, balance spring production, and case fabrication, all in a few square kilometers.

Innovation in Isolation

What sets the Vallée apart from other watchmaking centers is not just its output, but its philosophy. Time moves differently here. Watchmaking is less about trend and more about tradition. You won’t find the marketing flash of Geneva or the industrial scale of Biel. You find patience. Quiet. And mastery.

It’s no accident that some of the most intricate and idiosyncratic watches in the world have come from here- from Jaeger-LeCoultre’s Gyrotourbillon to Audemars Piguet’s ultra-thin perpetual calendar.

Even independent watchmakers like Philippe Dufour, the legendary craftsman behind the Simplicity, chose to live and work in the Vallée de Joux. For Dufour, as for LeCoultre, this region was the only place where true handcraft could thrive.

A Living Tradition

Today, the Vallée de Joux remains the spiritual and practical epicenter of Swiss haute horlogerie. It has survived quartz crises, globalisation, and market whims- not by changing, but by refining. By doubling down on what makes mechanical watchmaking meaningful.

In an era of smartwatches and instant gratification, the Vallée reminds us that some things—beauty, precision, tradition—can’t be rushed.

They must be made, patiently, by hand, in a cold valley where time was born. And this is precisely why I wanted to visit.

This would be my first visit to a manufacture and one that I will remember for a long time.

Arrival in the Vallée de Joux

My flight landed in Geneva, where I picked up a rental car and set off on the one-and-a-half-hour drive to Le Sentier. The route was spectacular, taking me up through the Jura mountains and down into the valley. It was the kind of journey where the scenery does most of the talking- rolling pastures, dense forests, and winding roads that feel like they were carved just for this purpose.

As I drove deeper into the Vallée, the excitement started to build. Along the way, I passed the manufactures of Audemars Piguet, Breguet, Blancpain, and others. Each one appeared modest from the outside, but their presence gave the entire region a quiet sense of significance. Finally, I arrived at Jaeger-LeCoultre.

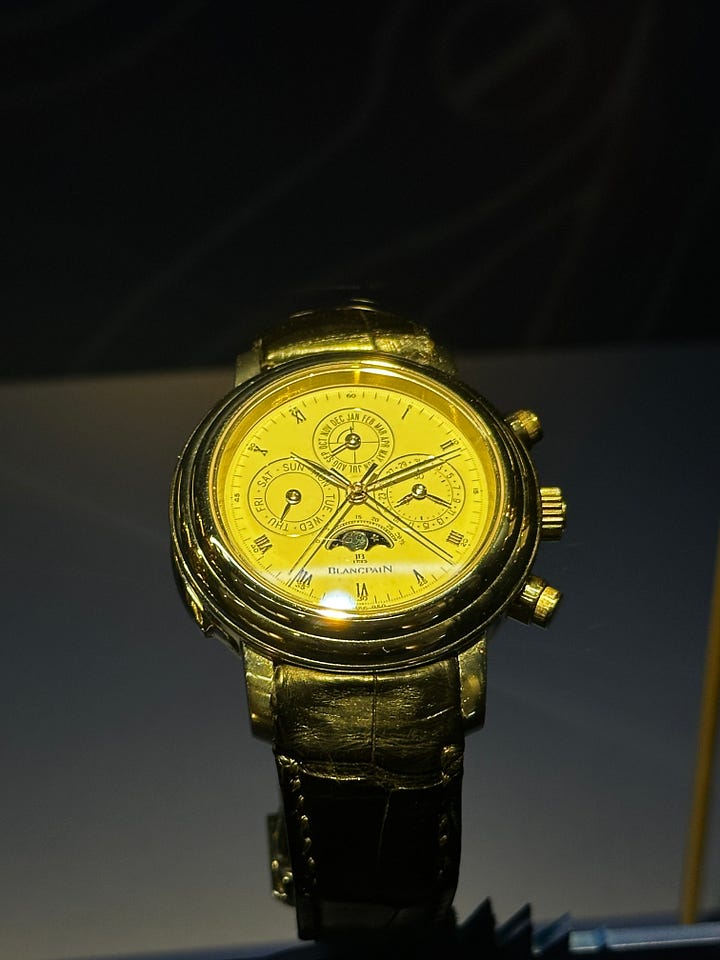

Once I had settled into the hotel, I decided to visit a nearby museum dedicated to the craft of watchmaking. Just a few meters from the Blancpain facility, the Espace Horloger is an absolute must for anyone visiting the area.

The museum houses an extraordinary collection of timepieces, all donated by the very watchmakers who live and work in the valley. Highlights included a Philippe Dufour, several Breguet and Blancpain watches, a handful of grand complication pocket watches, and a wide variety of ornate clocks. It was beautifully curated, intimate, and deeply educational. The most incredible thing is that the museum was almost empty. Here are a few of my personal favourites:

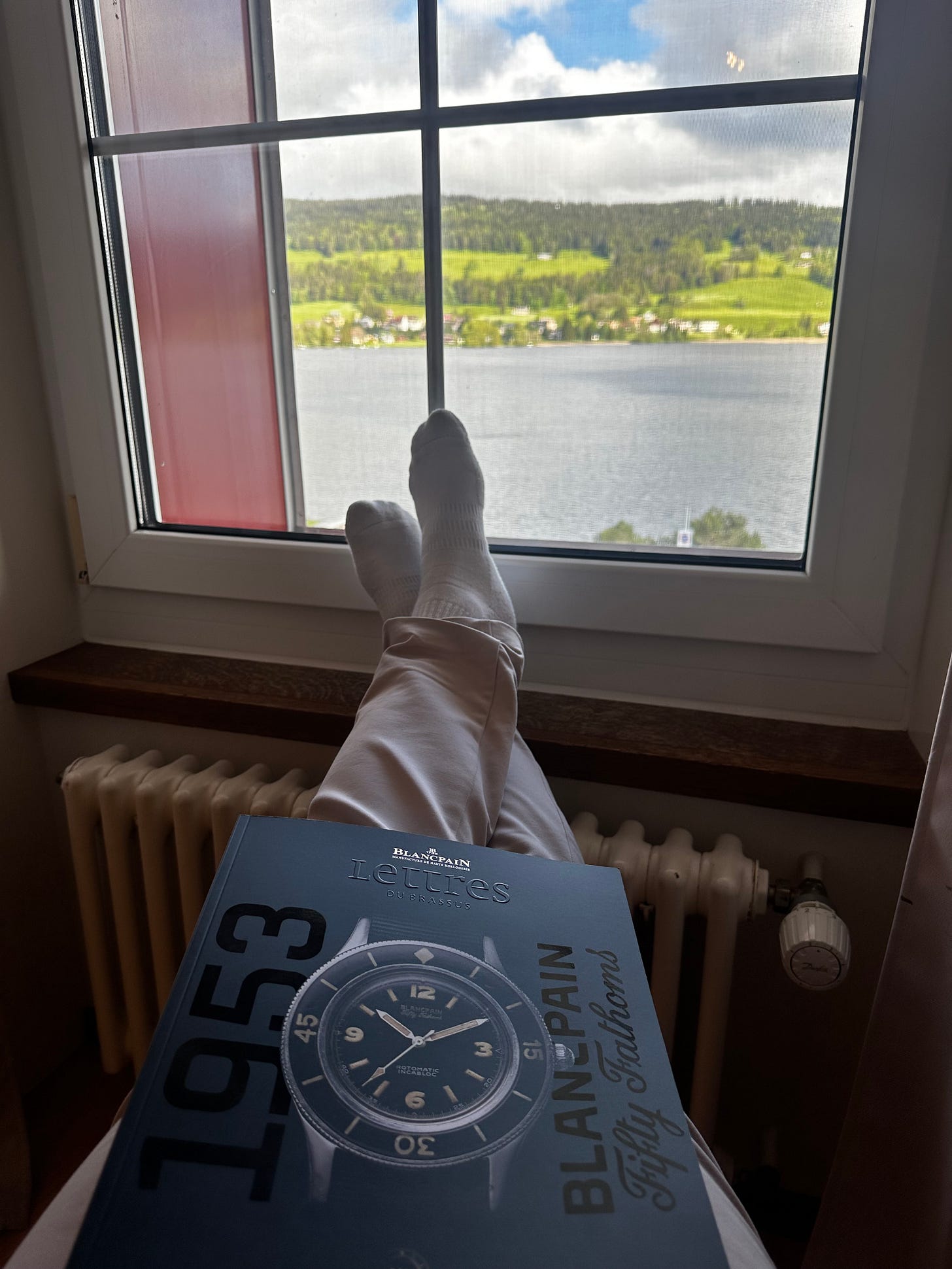

That evening, I enjoyed a well-earned steak and sat by the lake with a stack of Blancpain magazines kindly handed to me by the receptionist at the manufacture. The air was cool, the water still, and the mood reflective. It was the perfect end to the day.

The Reverso Discovery Workshop and Manufacture Visit

The next morning, I drove five minutes from the hotel to the Jaeger-LeCoultre manufacture. The factory’s facade was impressive- subtle but commanding, with an architectural clarity that felt both industrial and elegant.

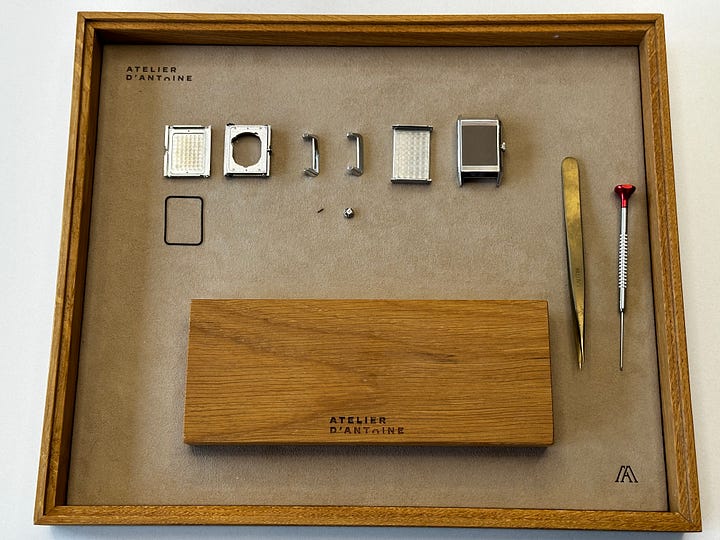

Our group was welcomed by a Jaeger-LeCoultre watchmaker and our guide for the day. The Reverso Discovery Workshop was held on one of the upper floors, in a well-lit room with sweeping views and a calm, focused atmosphere. In the center stood a large table, surrounded by eight workstations, each one set up with a miniature watchmaker's bench and a full toolkit. A giant model of the Reverso movement sat nearby, ready for dissection.

After some excellent coffee, pastries, and introductions, we got started. Our watchmaker began with a history lesson—first about Jaeger-LeCoultre itself, then about the Vallée de Joux, and finally the Reverso. It was a rich overview, giving proper weight to the story of a design that has remained largely unchanged since 1931.

The main activity of the morning was to assemble the case of a Reverso. We were guided through each step by the watchmaker, who was patient and incredibly knowledgeable. As we worked, we also learned about the finishing techniques that go into every watch. This included demonstrations of perlage and côtes de Genève, as well as an introduction to the art of enamelling.

Yes, I know I wore a Zenith Daytona- I promise I would’ve wore a JLC had I owned one!

Each participant was given the chance to try their hand at decorating a movement plate. The tools were simple but brutally unforgiving. I managed to create something resembling perlage- though I suspect the artisans at the factory would politely disagree.

After we had mangled our practice plates and gained a newfound respect for those who do this for a living, we broke for lunch. The afternoon would take us into the heart of the manufacture.

Unfortunately, we were asked not to take photos inside the workshops. This was not just to protect proprietary techniques, but more importantly, to respect the privacy of the artisans. And that felt entirely fair.

Jaeger-LeCoultre doesn’t just assemble watches. They create them, entirely in-house- from the tiniest pinions to the grandest complications. You feel this the moment you walk through the quiet corridors. The place isn’t flashy or performative. It’s methodical, almost monastic. Everyone you meet is focused, precise, and humble. It feels more like a guild than a business.

The Art of Making Everything

The first thing that strikes you is the sheer verticality of the operation. Most modern watchmakers outsource some part of production- cases here, movements there, dials from another region entirely. Not at JLC. Here, raw metal enters the building, and finished watches leave.

They cut their own gear wheels. They stamp and finish their own bridges. They build and adjust their own escapements. Each department sits just steps from the next. CNC machines shape parts with sub-millimeter tolerances. Those same parts are then passed by hand to artisans who still black-polish screws using traditional tin plates and diamond paste.

Decorative finishing isn’t an afterthought- it’s a discipline in its own right. There’s an entire room where watchmakers quietly perform chamfering, perlage, Geneva striping, and black polishing, each by hand. The contrast is striking: rows of silent benches, heads bowed, loupe to eye, hands moving slowly and deliberately. It’s hypnotic to watch. Some had been working on the same bridge or mainplate for hours. The patience is profound.

A Staircase to Complexity

The manufacture is organized across multiple floors, each representing a deeper layer of watchmaking. The further up you go, the more complex the work becomes. At the top, past sterile corridors and functional staircases adorned with oversized movement photography, you reach what can only be described as a sanctum.

This is where the grand complications are born.

Here, the most skilled watchmakers- each with over 15 to 20 years of experience- work on individual pieces, one at a time. Tourbillons, minute repeaters, celestial complications, perpetual calendars. Every masterpiece is the result of one pair of hands. It’s an old-school philosophy that’s rarely seen today, and it shows in the results.

No one here is rushing. There's no sense of deadline. A single watch might take several months to complete. These artisans aren't employees- they’re caretakers of tradition.

Movements Under the Microscope

One of the most memorable moments of the tour was when we gathered in a room for a masterclass led by one of Jaeger-LeCoultre’s senior watchmakers. Wearing a loupe permanently perched on his forehead, he walked us through several of the maison’s most iconic calibres under a high-magnification microscope, projected onto a large screen.

We zoomed in on the bridges and jewels of the Calibre 179—used in the Gyrotourbillon- and he explained how the spherical tourbillon, suspended in three dimensions, required an entirely new mechanical architecture. He then demonstrated a series of minute repeaters, letting us hear the tonal differences of each gongs’ material and shaping.

We learned how their minute repeaters are tested in a soundproof chamber for pitch, volume, and resonance. And how even the tiniest inconsistency in hammer alignment or gong curvature can affect the entire melody. The complexity wasn’t just mechanical- it was acoustic, aesthetic, almost musical.

The demonstration ended with a look at the Sphérotourbillon. As it rotated on multiple axes, the room fell silent. We weren’t just looking at a watch- we were witnessing an orbit, a little solar system in steel and gold.

A Manufacture That Still Makes Sense

In an industry often obsessed with image, Jaeger-LeCoultre’s factory tour is refreshingly unpretentious. There are no gimmicks. Just watchmaking. Real watchmaking. And an overwhelming sense of continuity- that what Antoine LeCoultre began in 1833 still defines the maison’s DNA today.

You leave understanding why the brand has been called “the watchmaker’s watchmaker.” Not because it’s a marketing line, but because it’s true. Jaeger-LeCoultre has historically supplied movements to Audemars Piguet, Patek Philippe, and Vacheron Constantin. But standing inside their walls, watching the process unfold from blueprint to escapement, it becomes clear they’ve always kept the best for themselves.

This isn’t just a factory. It’s a cathedral of craft.

And to walk its halls is to remember why we care about mechanical watches at all.

If you would like to book onto the Reverso workshop- just visit the link here.

This has been a pleasure to read. Thank you!

Sounds like a fantastic day! Thank you for posting.